[…]

Silence is music, too.

You can’t practice art.

In order for it to be true, one must live it.

Existence is not contingent upon thought.

It’s where you choose to put silence that makes sound music.

Sound and silence equals music.

Sometimes when I’m soloing, I don’t play shit.

I just move blocks of silence around.

The notes are an afterthought.

Silence is what makes music sexy.

Silence is cool.

[…]

Nicholas Payton

from On why Jazz isn’t cool anymore

Creating space in sound is crucial. Without space, soundscapes become cluttered and exhausting. Important information gets masked, sound quality suffers, and the experience can become irritating.

When we create space, the ear can identify information more clearly, more details can be heard, and we have greater control over tension and energy.

To create space, we must prioritize and sometimes let go of certain audio elements, even if we are attached to them. We have to accept stepping aside for the element that will tell the story better.

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

(Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Wind, Sand and Stars, 1939)

Embracing Space and Silence

Oh, the privilege of genius! When one has just heard a piece by Mozart, the silence that follows is still his.

(Sacha Guitry, Toutes réflexions faites, 1947)

Besides leaving room for other sounds, silence is important because it enhances both the sounds we’ve just heard and those we are about to hear.

When it comes to voice, silence is necessary between words and sentences. Sometimes, creative directors or narrative designers want to fill trailers or game sequences with spoken dialogue, even asking actors to speak faster or editors to shorten the pauses. This ends up sounding overloaded and unnatural. Silence, sound effects, and music are all part of the message we want to convey.

As for sound design: not everything needs to be heard all the time. Game sound is not reality, no matter how realistic we aim to make it. When walking through a city, our brain naturally filters out irrelevant sounds to focus on what matters at any given moment. Our work in game sound is similar: we direct focus to certain elements while pushing others into the background.

For example, when the main character is walking through a summer meadow on a calm day with no music playing, should we hear the details of their footsteps in the grass? Absolutely!

But when we’re racing a car at full speed with loud music blaring, do we want to hear birds singing in the trees? Probably not.

Composers must also exercise humility: sometimes stepping back by creating “musical ambiences” without dominant melodic lines, leaving a lot of room in their compositions, and skillfully adjusting instrumentation so that the full orchestra isn’t playing all the time.

And sometimes, the best solution is to have no music at all — letting voices and sound design carry the story.

Game Audio as Opera

I love to design game audio as a whole. Voices are the opera singers; sound effects and music are the orchestra in the pit.

All three are interconnected, working together to support the story unfolding on stage.

Sometimes, you’ll hear the soft murmur of strings like wind in the trees, then the melody of an oboe adding a pastoral touch — before the full orchestra bursts forth like a musical storm.

There are moments of intense energy, when singers and orchestra join in powerful tuttis; then quieter moments — arias that highlight the voice — and moments where just a few instruments play scattered notes surrounded by space.

How to Create Space in Time and Frequency Domains

Below is the kind of mental imagery I use when working on a game.

Of course, it’s not precise: sounds and music occupy wide frequency ranges. But it’s a useful approximation for communicating ideas.

Before:

We have a wind loop.

We have a music loop that fills a lot of the frequency spectrum, with little room left.

The music, wind, and footsteps often overlap in the same frequency ranges.

The result feels crowded, and some elements might get masked.

We need to make some adjustments.

After:

Instead of a constant wind loop, we have random gusts playing from time to time.

The music has been modified to leave more space and avoid occupying the entire frequency range continuously.

We can also apply a low-pass filter to the music, allowing sound transients to pass through more clearly.

This gives us more detail, more clarity, and a sound design that is less fatiguing over time.

We can also create dynamic EQ systems that temporarily attenuate certain frequency ranges.

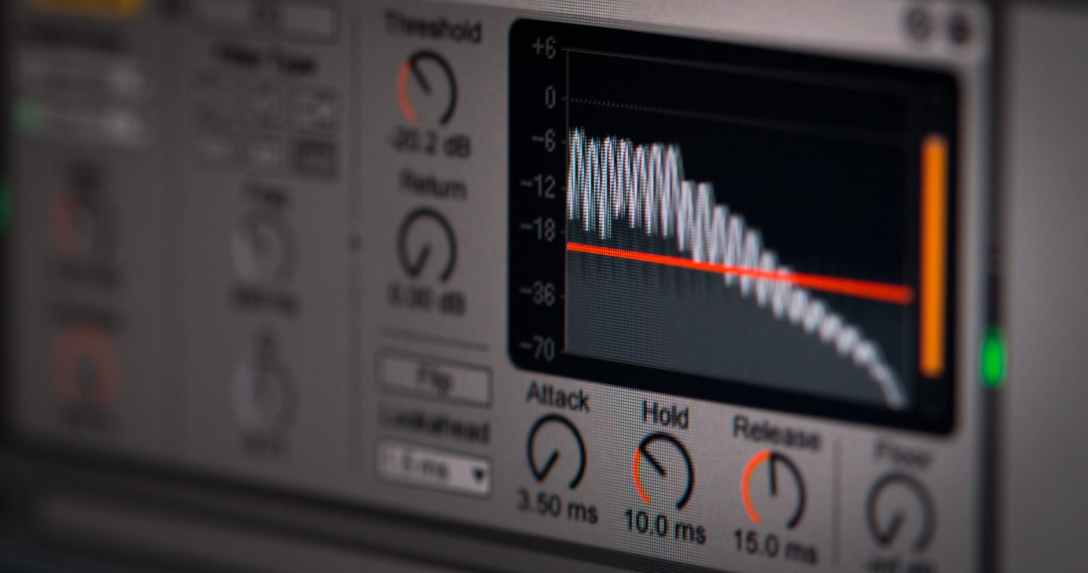

Creating Space with dynamic gain changes

Building voice, sound, and music systems while anticipating how they will interact and leave room for each other is important.

But we can also create space by playing with dynamics. Here are some examples:

- Auto-ducking the music and sound effects when dialogue plays.

- Dynamically adjusting the gain of music depending on game phases (e.g., number of enemies alerted), or based on the signal level of the SFX bus.

- Dynamically adjusting the intensity of certain instruments within the music depending on what’s happening in the game.